Getting to Yes – a book summary

Getting to yes is a book about negotiation. Don’t let that put you off as everyone is a negotiator. Negotiation happens every day, from agreeing the kid’s bedtime to buying a house and everything in between. Most of us learn negotiation through trial and error but there is a better way.

Getting to yes is a toolkit for negotiation based on 4 principles in a system they call principled negotiation. The principles are: “Separate the people from the problem.”, “Focus on interests, not positions.”, “invent options for mutual gains?”, and finally “Insist on using objective criteria when we’re going to resolve what it is we’re going to do”.

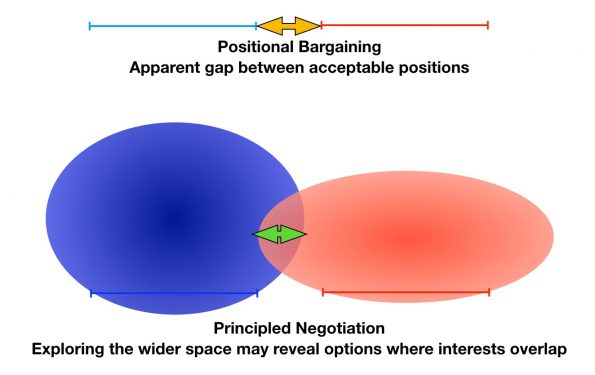

Principled negotiation is an alternative to positional negotiation. The approach of principled negotiation is advocated for by the Harvard Negotiation Project. Principled negotiation is about looking for mutual gains or a fair standard where there is conflict. It is hard on merits and soft on people. It works with any number of parties and issues.

Don’t bargain over position

Before going deep into the process of principled negotiation it is worth considering how to assess a successful negotiation. The book puts forward 3 criteria for assessing a negotiation:

1) Wise agreement – these ratify the parties needs and are fair and lasting

2) Efficient

3) Improve not damage relationship

The style of negotiation most people are familiar with is positional bargaining. This is like haggling over goods in a market. A positional approach to negotiation has a number of drawbacks. Focusing on positions removes any thoughts of alternatives as it tends to focus on a small number of factors (e.g. Price). Positional bargaining is harder where there are multiple parties and multiple issues as coalitions are often needed and this makes changes hard. A positional approach incentivises picking extreme initial positions to result in an acceptable settlement after a battle of will.

Separate the people from the problem

Conflict often lies not in objective reality but in peoples heads. People observe the world to build up their perception of reality but this is a subjective assessment. So put yourself in their shoes. Don’t deduce their intentions from your fears. Don’t blame them for your problem.

If the problem is rooted in different perceptions of the facts seek to work together to build an agreed set of facts – a shared understanding of the problem space. Give them a stake in the outcome by involving them in the process and give them credit for their contribution.

Emotions are another people problem that can complicate negotiation. There are 5 interests driving emotion in a negotiation

1) Autonomy

2) Appreciation (recognition)

3) Affiliation (membership of a group)

4) Role (meaningful with purpose)

5) Status

The first step to dealing with emotions is to recognise them, acknowledge them and try to understand their source.

Effective communication is essential for negotiation and communication is often a people problem in negotiation. Negotiators may not be talking in a way to be understood (intentionally or unintentionally). They may not hear you (active listening). Even when the parties are listening it is easy for misunderstandings to arise.

Play your role in effective communication: Listen actively and acknowledge what is being said. Ask for clarification if there is any uncertainty or ambiguity. Speak to be understood.

Good working relationships can prevent people problems from occurring – ideally, these should be built before the negotiation begins.

Focus on interests not positions

Wise solutions reconcile interests not positions. Your position is something you have decided upon. Your interests are what caused you to decide. Behind opposed positions lie more aligned interests than conflicting ones.

Ask why and build an understanding. Make a list of the other parties interests: this will help understand them. Ask questions to understand deeper. By understanding them you can help create options and solutions. Be specific about your issues. Look forward not back. Be concrete and flexible. Be hard on the problem and soft on the people.

The wisest solutions arise when both parties strongly advocate for their interests.

Invent options for mutual gain

Expand the pie before splitting it. Getting to yes puts forward 4 obstacles to an abundance of options in a negotiation:

1) Premature judgement

2) Searching for the single solution

3) Assumption of a fixed pie

4) Solving their problem is their problem

Overcome constraints by understanding them. Most people focus narrowly on the gap between positions rather than exploring the space in which principled solutions might lie.

To invent creative options:

1) Separate act of inventing options from evaluating them

2) Broaden options on the table

3) Search for mutual gains

4) Invent ways to make decisions easy

The book suggests brainstorming for solutions with a defined purpose and outcome. This should be done with a few participants (5-8 people) in a conducive environment with an informal atmosphere and ideally a facilitator.

It is important to collate ideas then evaluate them – do not evaluate in the ideation phase. Invent improvements to promising ideas during the evaluation and explore which to advance in the negotiation. Differences in interests and beliefs can offer unexpected win-win outcomes “Jack Sprat could eat no fat, his wife could eat no lean, so betwixt the two they licked the platter clean”

The key to reconciling different interests is to use options to explore what is preferable. Looking for low-cost to you, high benefit to them proposals and vice versa.

Precedents can help facilitate agreement: people like to be consistent so highlight past examples.

Consider from the others point of view – what might they be criticised for if the go with this option?

Creative inventing – generate many options – invent first, decide later, and seek to make their decision easy.

Use objective criteria

When interests are opposed don’t resolve by positional bargaining. This is a contest of who is most stubborn and is inefficient. Decisions based on standards make it easier for parties to formulate an agreement.

Develop objective criteria to assess options. There are a number of criteria which could be used (government standards, common practice, market rate, professional standards) so that parties will need to agree which standard or standards to use.

A way of testing the objectivity of the standards is checking if the parties are willing to be bound by the standards. A common example of this is with children sharing a cake – 1 cuts the cake, the other chooses the piece to have.

Acknowledge the potential for different views – high price v low price then jointly search for suitable criteria. Try to understand what rationale sits behind their position (e.g. comparable market rate) and then find the objective criteria to assess this.

The parties may need to agree on an objective basis for choosing between objective standards. “What standards did you use to arrive at that position?” What is the objective processes, standard or guide that is behind their position? Is there one?

Develop your BATNA

Often in a negotiation parties will establish a “bottom line” a position they will not pass to protect themselves from a bad negotiation. This makes it easier to resist pressure in the moment and prevents you making a decision you’ll regret.

However, this approach limits your ability to be flexible and learn during the negotiation, possibly ruling out more advantageous outcomes. A bottom line is often arbitrary. It is better to consider what are the alternatives to a negotiation? What will you do if you fail to reach an agreement? This can be used to formulate a trip wire – a minimum package above the bottom line. This is a point to reconsider your position.

A BATNA is your Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement – a better BATNA is more negotiation power. To generate a BATNA develop list of options (long list) of alternatives to reaching an agreement in the negotiation. Improve the promising ideas and assess how viable they are. Select the option that seems best – the one you will fall back on. You now have a BATNA to consider offers against during the negotiation.

You may wish to disclose your BATNA during the negotiation – this is a case for judgment. Disclosing your BATNA will highlight to the other party your alternatives and may also indicate interests they can meet which you have not articulated.

It is useful to consider other sides BATNA. It might be better for them than anything you can offer. It might be unduly optimistic and you can help them see that.

“If the other side has big guns you don’t want to turn the negotiation into a gun fight”

What if they won’t play?

How to turn from positions to merits: change the game by playing a new one. Keep practicing principled negotiation, seeking to understand the interests behind their positions. Principled negotiation can be contagious.

If principle negotiation does not catch it may be necessary to practice negotiation jujitsu. If they push hard and you push back you end up at positional bargaining. So don’t reject their position, side step, channel the force into exploring options.

Attacks have 3 types: reinforcing their ideas, attacking your ideas, attacking you. Don’t attack their position: look for the interests behind it. Assume their position is a reasonable way to meet their goals. Direct their attention to improving their position. What would you (the other party) do if this package was accepted? How would it be implemented? Does this really give them that they want?

Don’t defend your own ideas: accept criticism, in fact, invite it. Ask them what concerns (interests) of theirs this package does not take into account. Mine their response for underlying interests.

You can sometimes turn the situation around by asking them for their advice: in my position what would you do?

Recast an attack on you as an attack on the problem. Statements generate resistance, questions generate answers.

Ask questions and pause: silence is one of your best weapons. The other party often feels compelled to fill the silence.

If the jujitsu does not work it might be necessary to invoke the one text procedure. In this approach, a mediator separates the people from the problem moving to interests and options. The mediator works with the parties separately to determine what their underlying interests are. They then assemble a list of interests and options and asks the parties to review it (this is the one text).

The one text technique reduces the number of decisions. The third party creates a proposal and then invites critique from both parties. It iterates until 3rd party can’t revise and improve the package. This is then recommended for acceptance.

Helpful phrases

Please correct me if I’m wrong – this invites corrections and validates assumptions – this is a pillar of principled negotiation

Our concern is ____ share a principal and sign post drivers around which negotiation can happen.

We’d like to agree on a basis of independent standard

And not but (I could write a whole blog post on the benefits of this simple substitution)

Could I ask you a few questions to see if my facts are right?

Ask a question don’t state facts – build a foundation of agreed facts

Let me see if I understand what you are saying – confirm understanding and demonstrate that understanding

Let me get back to you – distance and time help to separate people from the problem.

Present reasons before stating a proposal

One fair solution might be – does that sound fair?

What if they use dirty tricks?

I must confess to paying less attention to this section as I have not (knowingly) negotiation with someone invoking dirty tricks. Getting to Yes has 3 steps to negotiating the rule of the negotiation when the other side uses dirty tricks

1) recognise the tactic

2) raise the issue explicitly

3) question the tactics legitimacy and desirability

In conclusion

The book organises common sense (the authors said that not me). While some of the technique may only be suited to formal negotiation many of the recommendations can help to bring clarity to everyday communication. The book points in a promising direction but one must learn by doing.

Pingback: A new approach to reading business books – Differently Wired